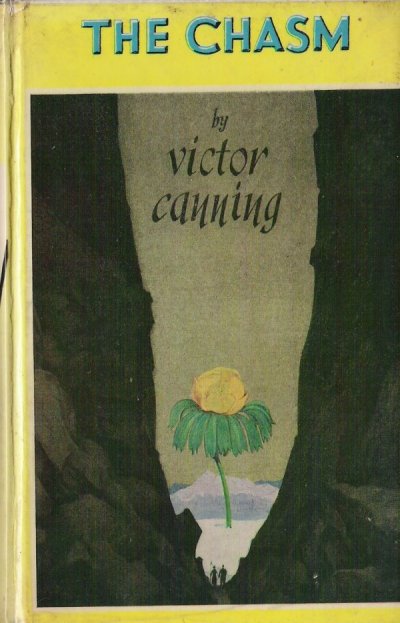

First edition 1947

US First edition 1947

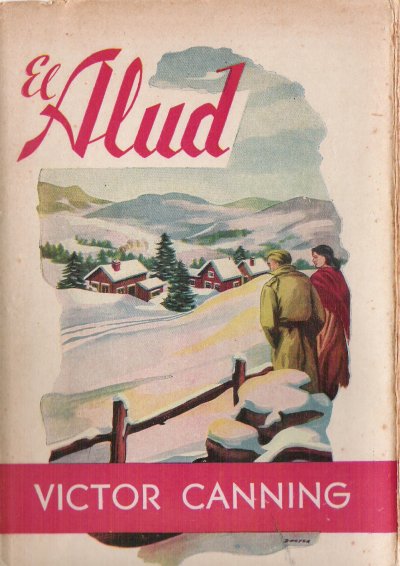

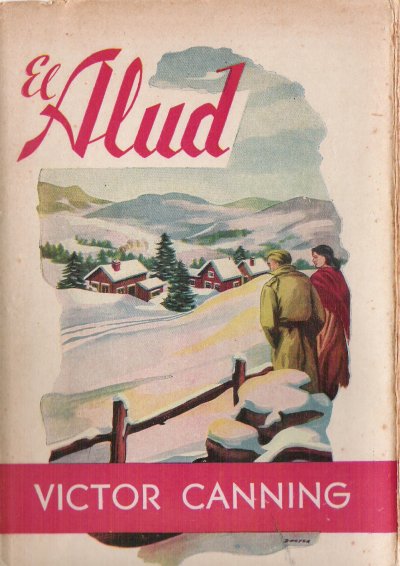

Spanish translation 1948

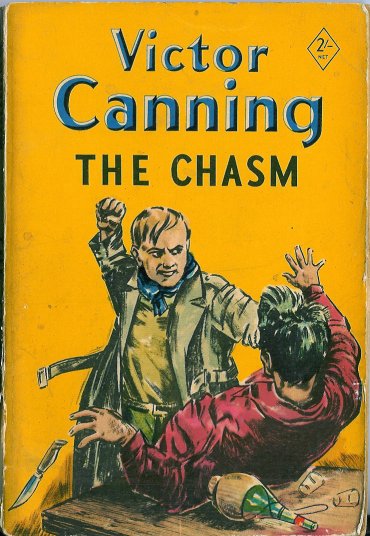

H & S paperback 1952

1960 paperback

US paperback

First edition 1947 |

US First edition 1947 |

Spanish translation 1948 |

H & S paperback 1952 |

1960 paperback |

US paperback |

The BookThe book is dedicated "To C.J.B.M., W.D.S, and P.F.C." One presumes these are wartime colleagues, and one of them is probably the shell-shocked officer he met in Florence, though nothing can be said for certain. The main character is Edward Burgess, a discharged and rather shell-shocked officer now working in Italy as an architect for UNRRA, enjoying a week of sick leave in Florence in February 1947. He keeps seeing people he thinks he knows. He remembers a pre-war visit with some British university friends, and sees a man who reminds him strongly of one of them, William Martel, last seen fifteen years ago, but this man is an Italian art dealer with a badly burned face. Burgess makes a nostalgic journey into the mountains. He meets a young woman, Gemma, and a boy driving an oxcart across a rickety bridge over a ravine. The bridge collapses, trapping them on the far side, so Burgess must stay in their village until the bridge is mended. He is introduced to the local landowner, Signor Riccioni, who turns out to be the same art dealer he met in Florence, and is now definitely recognised as Martel. But Martel/Riccioni is a Nazi collaborator hiding in Italy and wanted for treason. Riccioni, realising he has been recognised, is determined to have Burgess killed before he can leave the village and report his whereabouts, and calls on the services of Bista, Gemma's fiancé. Meanwhile Burgess and Gemma have fallen in love, and a confrontation looms. |

Publishing historyThis was published by Hodder and Stoughton in 1947 at 9/6 with an initial print run of 15,000. It was reprinted in 1951 at 5/- with another print run of 15,000. An abridged paperback came out in 1952 with a print run of 60,000. These were much larger runs than Canning had enjoyed before the war. An American edition was published by M.S.Mill in 1947, and was a Book League of America selection for 1948. An American paperback appeared in the mid 1950s. The film rights were sold to Columbia before publication, and there were plans to film it in Nettlefold Studios under the title "Monte Falcone" announced in 1946, but the plans seem to have been abandoned and no film was ever made. It was the first book Canning wrote after the war, and followed a four-year gap since Green Battlefield in 1943. It is a halfway house between the novels he had written in the thirties and the thrillers that would become his stock-in-trade in the fifties, mainly a tragic love story, but with thriller elements. In a publicity handout from 1952, he describes how he came to write it.

The route Canning describes in the book shows Premilcuore as the

best candidate for 'Cappa'. An academic paper from 2014 by Stefano Piastra confirms this and proposes the village of

Corniolo for 'Montefalcone'.

|

|

|

|

| (Expulsion of Adam and Eve by Masaccio, before and after cleaning in 1980.)

Burgess was glad to be left alone. He stood looking up at the figures of Adam and Eve quitting the Garden. He could

remember Rich’s excitement clearly. Yet, somehow, standing here was not the same as he had thought it might

be. Rich was not here, only the thin echo of him. Here, before the work which had kept Rich, in his odd, enthusiastic

way, talking for days when they had seen it on their holiday as students, there was only the echo of the man, not

the vividness of his presence which possessed Burgess so often in other places. He could recall the excited voice

only, declaiming Milton’s lines: ‘The world was all before them, where to choosePage 2 |

(View of the Arno looking towards the Ponte Vecchio, 1945 from Firenze: gli anni terribili, Bonechi, 1969) This moment of twilight was one he loved most in the city. The growing mist shut from view the Bailey bridges which had long replaced the ancient and lovely structures destroyed by the Germans. The recital of their names was a rich litany to one who had known the city before the war, Ponte alla Carraia, Ponte Santa Trinita, Ponte Vecchio, Ponte Alle Grazie … now only the Ponte Vecchio remained. Page 3He crossed the foot of the Bailey bridge at the Ponte Santa Trinita, wondering what special torment would be reserved in hell for the men who had destroyed such loveliness. Dante might perhaps be allowed to suggest some new horror for them. Page 13 |

(La Maddalena by Francesco Bacchiacca, Sala di Prometeo, Palatina Gallery, Pitti Palace.)

Burgess studied it slowly, memory coming back upon him as he did so. The saint was leaning slightly forward, her long, pale fingers clasping a veined alabaster jar of unguent. Her hair, tightly braided, fell away from the fine broad forehead in tawny tresses over her shoulders. Crowning her hair was a richly jewelled circlet set with tiny pearls. The eyes were dark and gave to the long face an expression of quick, human interest, the face of a woman who knew her own strength. And yet, about the lips, hung the slight, nervous questioning of a child that does not understand, an innocence refined into a spirituality by the pallid lustre of her skin. Burgess remembered, as the problem of interpretation presented itself again to him; that time, so long ago, when they had all our stood before it. It had hung even then in this position. To each of them the picture had spoken differently. He and Harrison gave their views without heat or conviction. Between Rich and Martel there had commenced an argument, fierce, and yet subdued by the necessity of keeping the voice low and orderly in the gallery. Page 24 |