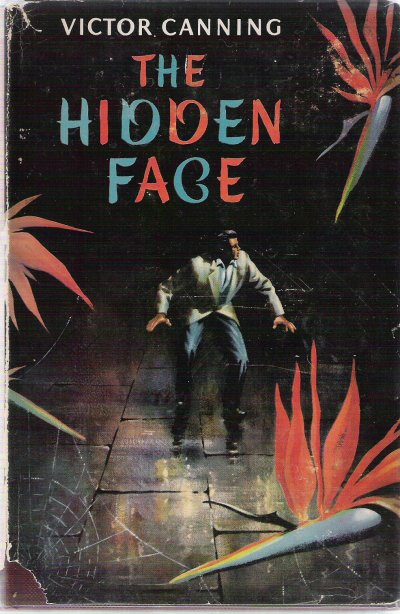

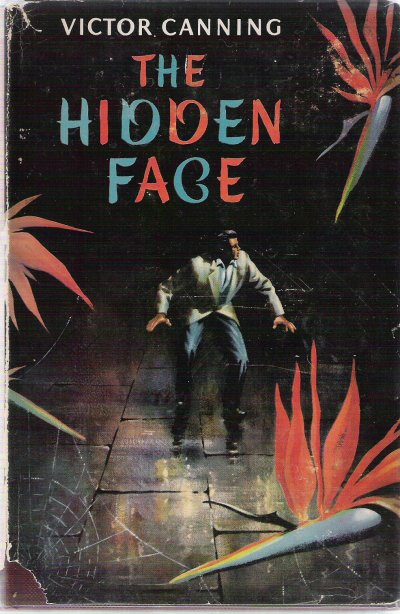

First edition 1956

First US edition

Hodder paperback 1960

US paperback

Uniform edition 1973

Simplified version

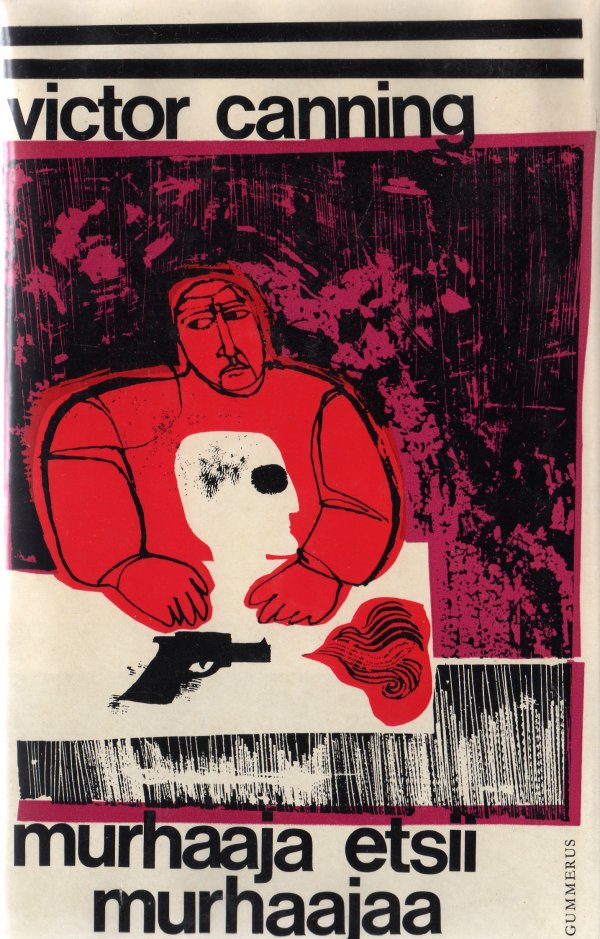

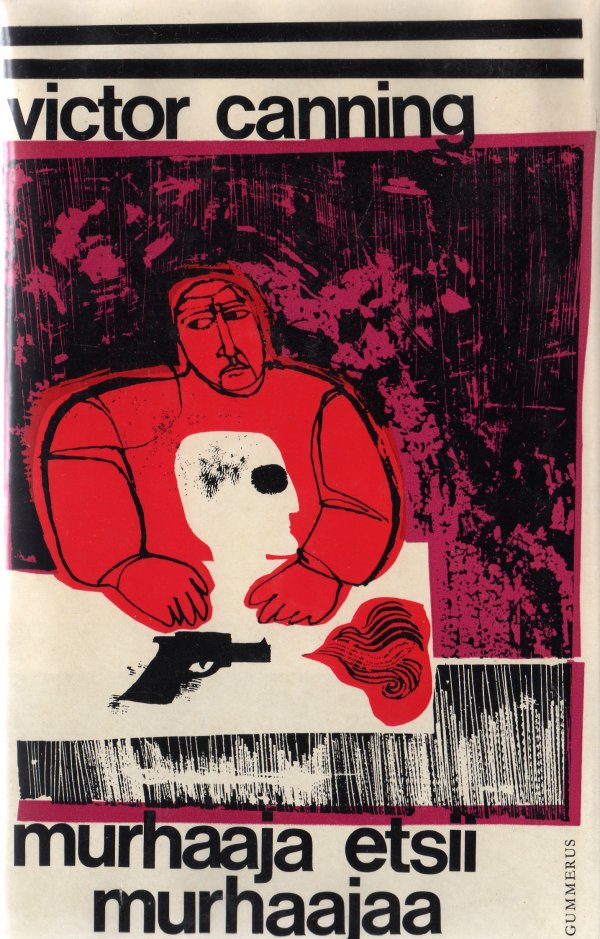

Finnish translation

Alfred Hinds's book

First edition 1956 |

First US edition |

Hodder paperback 1960 |

US paperback |

Uniform edition 1973 |

Simplified version |

Finnish translation |

Alfred Hinds's book |

The BookThe book is told as a first-person narrative (unusual for Canning) by Peter Barlow, who is convicted of murder after visiting and threatening Hansford, a man who had been blackmailing Barlow's late father. After serving two years, Barlow is sprung from Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight by an old friend, Ross-Piper, and his lugubrious manservant, Drew, so that he can identify the real killer. Waiting at a safe house, he meets Catherine Swinton who is escaping from an amorous boss. She comes with him on the escape boat, helping him foil a murderous attack by two men on the beach just as the boat arrives. Once on the mainland, Barlow tries to track down people who knew Hansford. He escapes another attack by hiding in the Palm House at Kew Gardens. He finds out that the murder of Hansford was mixed up with the forging of British and American currency using plates created by a Jewish artist who has worked on Operation Bernhard, a Nazi scheme originally based at Sachsenhausen and later at Redl-Zipf. The artist is now living in north Wales, so Barlow sets off for Wales with Catherine, with whom he is now in love. There are confrontations and explanations. The good end well and the wicked end badly, but only just. It is sometimes hard to swallow the implausibilities in the plot and thinness of characterisation, but these are redeemed by some fine descriptive writing and by effective set pieces of action in the prison and at Kew Gardens. |

Publishing historyIt was published by Hodder and Stoughton in 1956 at 10/6 with an initial print run of 11,500, and was issued in a combined book club edition Castle Minerva and The Hidden Face by the Companion Book Club in 1957 at 5/-; it is fairly common in this form. There was a paperback in January 1960 at 2/6 in a print run of 30,000. In 1962 there was a simplified version for EFL learners by University of London Press. In 1971 there was a Heinemann uniform edition at 18/-, reprinted in 1973 at £3.90. The American edition by W Sloane in 1956 was titled Burden of Proof. It was serialized in Everybody's in eight parts from 12 March to 30 April 1955 and in various US newspapers in November/December 1955. Both serialisations were under the English title The hidden face. The book was adapted for radio by A. Elliott Cannon and presented twice with different casts, first on the BBC Home Service on Tuesday 14th June 1960 with Irene Sutcliffe and Simon Lack, and again in the series Saturday Night Theatre on Radio 4 on Saturday 23 January 1971 with Andree Melly as Catherine Swinton and Kelly Francis as Peter Barlow, produced by David Geary. It was also twice read aloud on the BBC Woman's Hour, the first time from 12 February 1958, abridged by P.J.Wright in 12 episodes read by John Westbrook, the second time in 11 episodes abridged by Madge Hart, and read by David Macalister from 17 November 1982. Escaping from Parkhurst Prison also featured in two of Canning's short stories, "It never pays off" and "Breakaway". We know from a 1966 newspaper interview that Canning was interested in the exploits of Alfred Hinds, a prisoner who had escaped from several prisons in the 1950s including Parkhurst, calling Hinds's book Contempt of Court "good background stuff for what I write". |

Victor Canning was careful to research his plots, and had obviously "walked the course" that he requires Peter Barlow to run on his escape from Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight. Photography is prohibited in the immediate area of the prison, but here are some pictures of locations mentioned in the early chapters.

|

|

|

We were in Nicholson Street—named after a former governor of Parkhurst Prison. Twenty yards away a green bus came slowly down Horsebridge Hill on the main Cowes-Newport road. (Page 17) |

|

|

|

|

I was in the trees. Five minutes, and another ten to go before the patrol cars would be along the road towards the Pallancegate. Five yards inside the wood I turned right-handed and began to run parallel to its edge. The young bracken was just unfurling and the ground was covered in a litter of dead pine needles and leaves. I swerved deeper in, careless of the noise I made, to avoid the Forestry Commission gateway. (Page 23) |

|

|

|

|

We came down to it through narrow, twisting lanes and then out on to a wide military road that ran the length of that lonely coast. The road ran along a red brick viaduct that spanned the stream running down Grange Chine to the sea. (Page 45) |

The cliffs at this point were fairly high, going up nearly two hundred feet. The path climbed through patches of loose crumbly earth and chalk. About twenty feet from the top of the cliff it came to an end. Recently part of the cliff had fallen away and taken the top part of the path with it. A long slide of mud and loose stones dropped away to the beach, leaving about three square yards of turf platform with a couple of gorse bushes. (Page 48) |

The actual address, 27A Kew Green, does not exist, but Canning describes the Green and Kew Gardens accurately. The admission that Peter Barlow pays is threepence, recently raised from the post-war price of one penny. It is now (2024) around £20, more than a two-thousandfold increase.

|

|

|

… a Lieutenant-Colonel Drysdale. And he lived at 27A Kew Green, Kew. He was the man I was going to see. … The only time I'd ever been to Kew before was when I was twelve and my mother had taken me to the Royal Botanical Gardens. I didn't remember it well. I walked across Kew Bridge to the Green. It was large and triangular shaped, surrounded by trees and on two sides by old houses still wearing a faint look of surprise that they should be allowed to carry on their village existence in London. … Number 27A was about half way up the road,; a little white-faced Queen Anne house with a green ironwork balcony roofed in the shape of a scallop shell on the first floor. (Pages 82-3) |

|

|

|

|

At the black and gold wrought iron gates I paused. There were very few people about for the rain had driven them from the Gardens. … I went in and up the main walk and suddenly from a tree a blackbird began to sing, a lusty boisterous sound in the wet evening, and it did nothing to cheer me up at all. Underneath one of the bushes a couple of moorhens were raking in the soft ground for grubs. I remembered the moorhen that had called on the night Hanford was killed. And grimly I acknowledged that one of these might well call on the night I was killed. (Page 96) |

|

|

|

|

I hurried up the path past the great glass structure. A notice board said Palm House. There was a small door at the far end, and it was open. I slipped inside, unseen by my followers. … I came out of the wet English summer evening into a tropical forest. Great palms and green growths soared up to the roof. The air was hot and steamy and there was a warm, rich, fruitful smell of damp earth. (Page 98) |

|

|

|

|

It was almost midnight. In the great sweeps of vegetation the shadows were more defined. Then I caught the sound of footsteps. … I moved back between the tubs, treading softly. Here was an iron-runged ladder which went up to the roof of the transept to a small railed platform. … I lay there with my head peeering over the platform, watching the torch. It swept round in a slow circle, away from the ladder and then back. It stopped, and looking down, holding my body in tensed immobility, I saw why it had stopped and cursed to myself. On the wide flat rungs at the bottom of the ladder the light was shining on the wet marks my feet had made on them as I climbed. (Page 102) |

|